Yuge Zhou

*Reaching for the Other Side

interview & written Mariepet Mangosing

Yuge Zhou got her start as a popular child singer in China, where she starred in many different television shows.

It was during this time as a performer when she quickly learned that she is a born storyteller, though she would later realize that entertainment was not her end-all be-all. She shares, “The experience of performing on stage planted a seed in my heart of wanting to touch people with my own expression.”

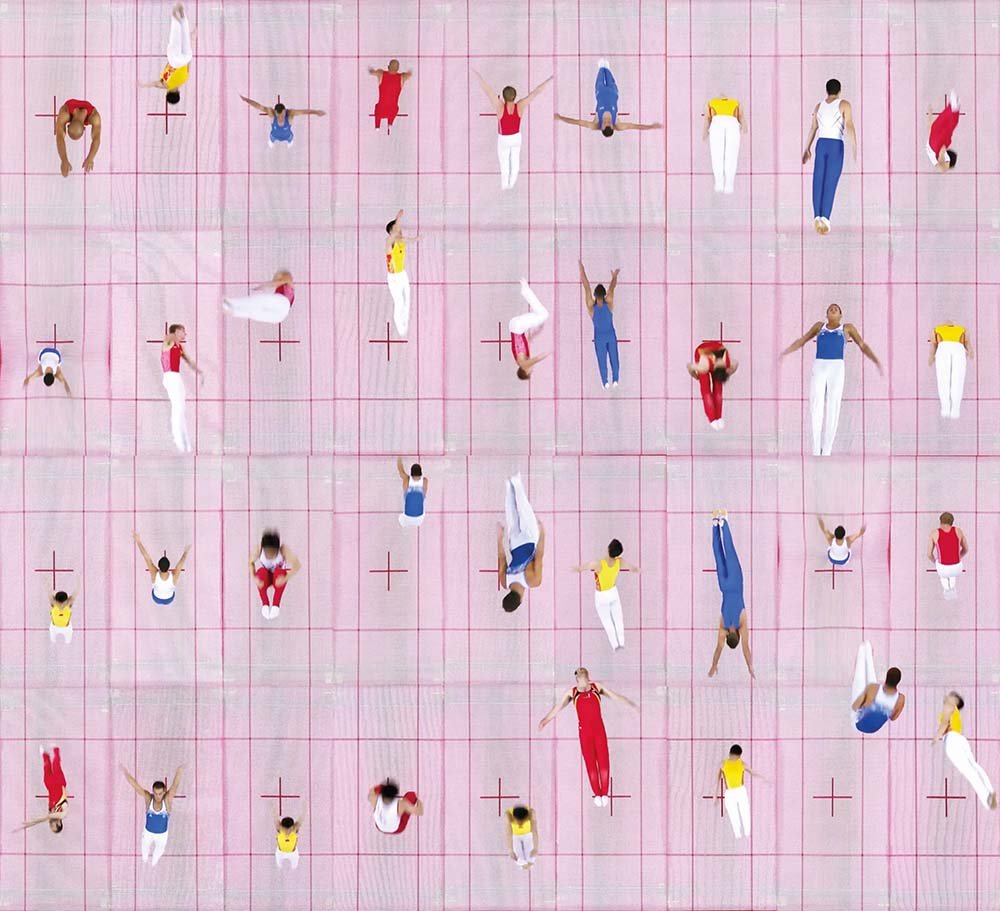

Trampolines Color Exercise

© Yuge Zhou

After leaving China and moving to the United States, Zhou “picked up a camera and started shooting,” which ultimately led her to school. She says, “I went to pursue an MFA at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, where I was able to fuse artistic concepts with the logic associated with technological innovation.”

Not wanting to use conventional structures to tell stories the way films and television do, Zhou began to utilize “non-linear structures that can best be explored through video installations.” Thus, an experimental video artist emerged. She continues, “I find that with video art, I can envelop the viewers with moving images, color, light and sound within a physical or virtual space or place.”

One of Zhou’s main preoccupations is observing humans behaving and gesturing at each other, a subtle communication that is often more powerful than any exchanged words. When approaching her subjects, she explains, “I first notice how people behave as well as their mannerisms, both as individuals and as groups. I’m observing through my own lens so how I read people and my response to them says as much about me as the people I encounter.”

While the distant point-of-view belongs to her, Zhou observes with a sense of intimacy and closeness that directly juxtaposes the vantage point, moving through her work, threading the overall plot and theme scene by scene.

“A lot of the fragmented scenes in my video collages are connected via the flow of gestures. Because there’s no language in my work, gestures are like words that give meaning to the micro-narratives that I ‘stage.’ Ultimately, I’m interested in showing the beauty of human behavior and sometimes its absurdity.”

Pale Patrol (The Humors, part four)

© Yuge Zhou

When the East of the day meets the West of the night (video still)

© Yuge Zhou

When approaching theme, Zhou leans on her bicultural background. “I feel that, at times, I am too Chinese to be American and too American to be Chinese,” she says. “I also find myself longing for home and realizing that both countries are my home. I will always exist in these two cultures as both an outsider and an insider. You can see it from the way I position myself in my work.” Zhou asserts that her identity, centered around this idea of feeling forlorn and desiring roots, is at the helm of anything she does. She comments, “What is interesting after all these years is that I feel like the in-between, this gray area, is actually what is most interesting for me. Now I’m at a place where I’m happy with that. I’m willing to explore this in-between state rather than trying to find one or the other.” In one of her latest series, The Humors, she shoots subjects from an aerial view. She notes,

“The scenes are all filmed from a distance, as I have positioned myself as an observer of the actions, isolated. That has a lot to do with me feeling disconnected from activities but at the same time interested in the connections captured between people.”

Moon Drawings, 2022

© Yuge Zhou