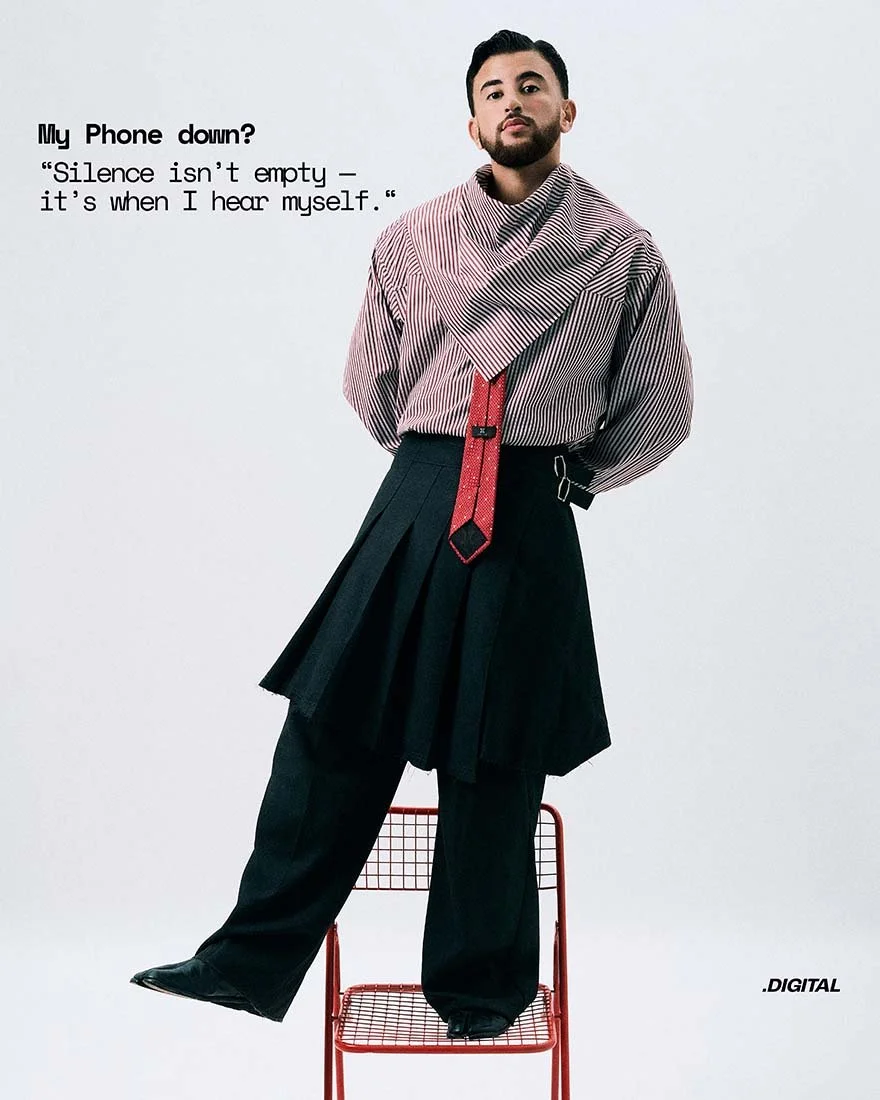

Technical Romanticism

How Josh S. Rose photographs Performance as a Technical and Human Act

written + interview JONATHAN BERGSTRÖM

Josh S. Rose is a visual artist and storyteller working across photography, film, and writing. His practice brings together visual and performing arts, centering on movement, emotion, and image. Recognized for his collaborations with leading visual artists, choreographers and dance institutions, Rose has built a unique artistic language that captures other art forms, especially performance, as both a technical feat and a deeply human experience, an approach he describes as “technical romanticism.”

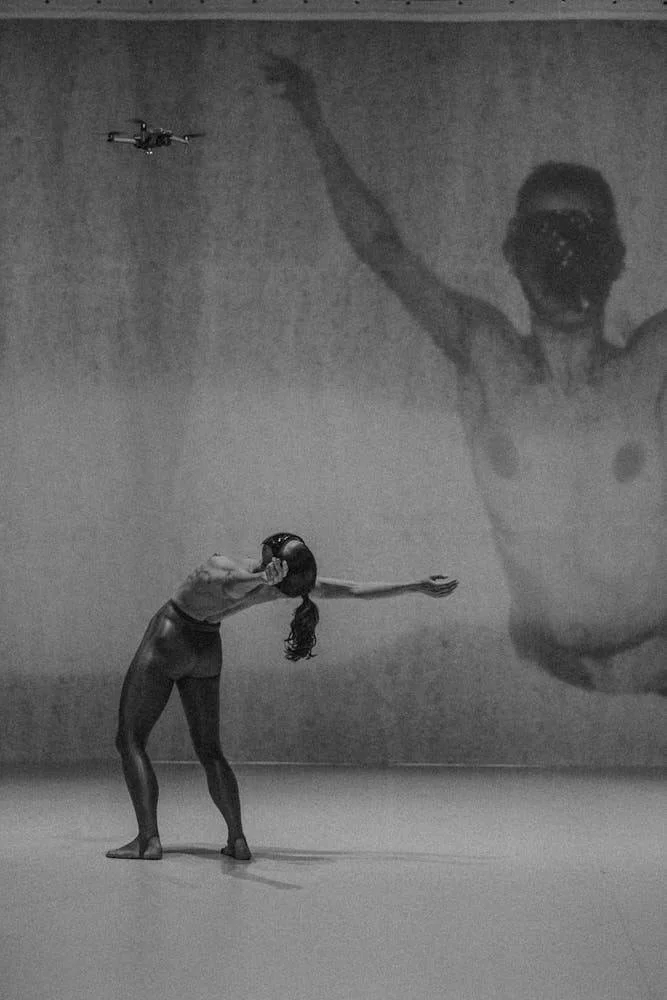

Lenio Kaklea / The Birds

Performance documentation at MOCA November 2025

Performer Nefeli Asteriou

seen by Josh S. Rose

courtesy of MOCA

From photographing Lenio Kaklea’s The Birds to developing contemplative series such as Tired and The Standouts, Rose turns his lens toward how bodies move through space, time and social expectation. Whether documenting choreography, tracking the passage of daylight, or observing everyday gestures, his work focuses on the patterns and interactions that shape each moment. In this interview with LE MILE, Rose discusses the trust required to document dance, his approach to experimentation within live performance, and the ways repetition and observation inform his evolving work.

Jonathan Bergström

How did you come to photograph The Birds by Lenio Kaklea?

Josh S. Rose

This is one of those things that happens in a minute, but really over years. Kaklea’s piece was coming to the States for the first time and being performed at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Dimitri Chamblas, a longtime collaborator and prominent choreographer and artist, recommended me to shoot it, as they were looking for someone who could jump in and capture the essence of the piece. Almost every performance I capture happens either with someone I have worked with a lot, or recommended by them. Dance is very personal and needs to be captured with care, but also very technical. The light is always changing, the movement can go from fast to slow and a shape comes and goes very quickly. I’m often seeing it for the first time with the audience. So, I’ve built up the kind of trust over the years that makes me a viable person to explore still photography during a performance like this.

When photographing choreography, what visual moments are you paying attention to?

Most choreographers who design for the stage are thinking about a mix of things: there is the meaning of the piece that is expressed through blocking, movement, shape and the interplay of dancers, but there is also wardrobe, art and lighting that help define that concept. Incredible works, like what Kaklea has created, have other things going on, too. At one point, she had a performer fly a drone and projected the drone’s view to the backdrop of the stage. In another, a trapeze hangs from the ceiling. Chamblas, who I mentioned earlier, does a piece with a giant floating balloon structure above the stage. Los Angeles Dance Project has a piece running that uses artwork from Barbara Kruger.

I often shoot dancers performing in and around art installations. So, I try to understand what it is that is trying to be impressed upon the audience and then heighten or accentuate that. I’m very interested in where the interplay of these elements happen. I like to find compositions within those juxtapositions. It’s like shooting a meteor shower or something. Every shot you take is different and you have to be okay with that and accept that a lot of this is stochastic. You’re in the design, so there is no bad shot. You don’t think in terms of good or bad, but rather in deeper explorations of the meaning of the work. It’s interesting that Kaklea’s piece is called The Birds, since birds are a great example of natural patterns of design. For whatever reason, I am very comfortable in a space like that, if not entirely amazed and inspired by it. I think that excitement and curiosity fuels how I see and shoot.

Lenio Kaklea / The Birds

Performance documentation at MOCA November 2025

Performer Jaeger Wilkinson in the back Louis Nam Le Van Ho and Amanda Barrio Charmelo

seen by Josh S. Rose

courtesy of MOCA

How do you balance documenting the work with expressing your own visual style?

My own style is a bit more experimental, or maybe looser, than it is straight documentation. Though when shooting a performance, I make sure I honor the work put into the production. Often what will happen is that I get inspired to try something within any performance and take the time to explore it. Sometimes that is literally two different cameras, but more often it’s a quick idea in between something more formal.

When I am being more expressive in my shooting, I like to experiment with double exposure, filters and often I will mess with the horizon line or find a surprising or unconventional composition. I think of these as tools for emotional expression. I think my visual style is a result of that personal approach, where my own chaotic-curious way of shooting meets the frenetic-emotional nature of dance. When it hits right, I think it sits at the edge of abstraction and that is what makes it beautiful. A certain level of unknown in art is meaningful because it leaves some things to the imagination, plays in the dark and feels wild and free. Often you have to fight against the exactitude of photography to achieve that kind of work.

Let’s talk about Tired. Why did the sun’s passage across the sky feel like the right structure for the project and what did committing to the full arc of daylight reveal that a single moment could not?

Tired is also about movement. But in this case, it is expressed through time. To feel the sun move, not by looking at it but by seeing how it changes something static, seemed like an observation worth pursuing. I became aware while shooting it that I was spinning, or the Earth was spinning with me on it. The interplay of movement here only happens if you sense the sun’s movement, or, in reality, ours. Once that idea entered into the equation, I could no longer see the piece without the narrative element of time.

I think with Tired, the visual is so arresting. This pile of tires is immediately metaphorical. If you look at two shots of it, the movement of the sun is actually hard to notice at first. But that’s what is interesting to me. You have to ask why it’s being duplicated. When you see the difference and focus on the subtleties, that’s when the idea reveals itself. I like an image or series that invites you to explore it. Less immediate, but the potential to reveal more.

You mention the contrast between movement and stationary objects whose purpose is movement. How did that idea guide the project?

I mean, who doesn’t feel a little run over by the wheels of time? Especially these days. This is the flip side of moving, of the revolutions we go through in our lives, of aging. I think we look at tires and think, yeah, that’s me, too - round and round and round. I just wanted to make sure that idea hits you when you look at it. You might have felt a bit of that with just one image, but spread out the images over time and I think it becomes an unavoidable takeaway.

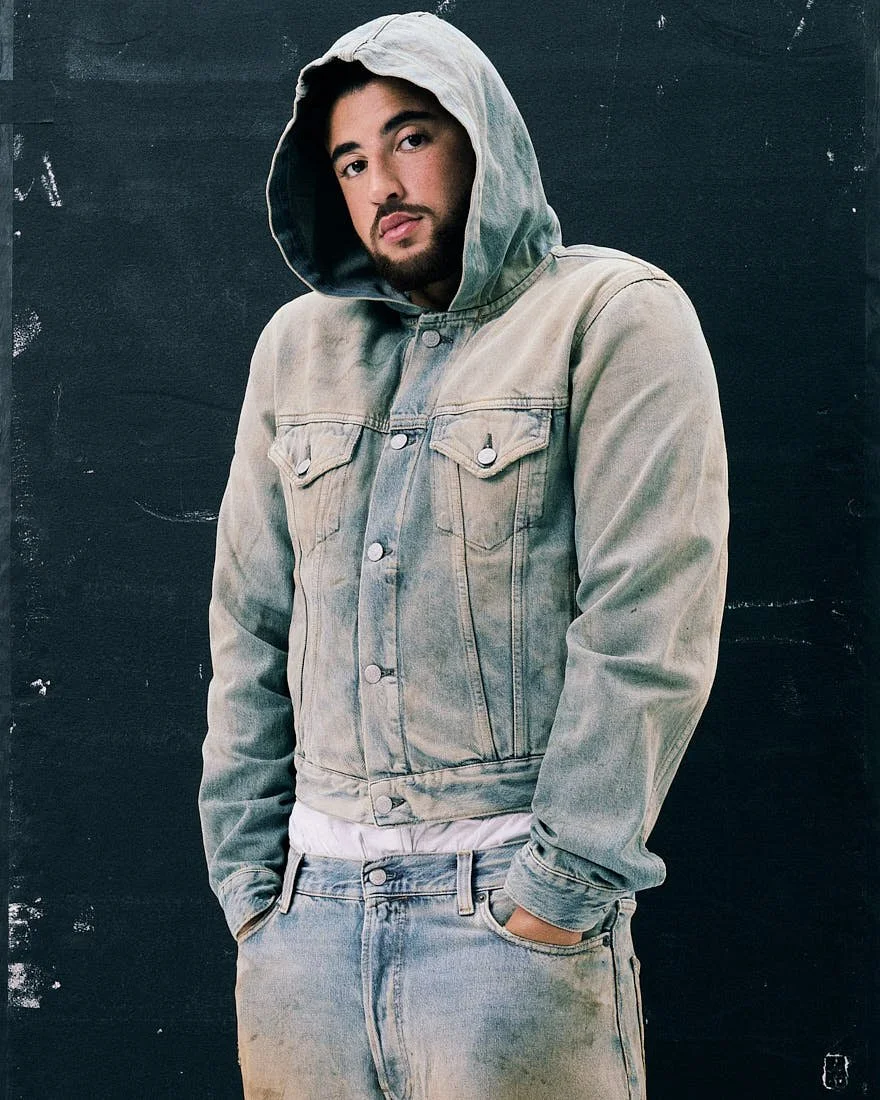

The Standouts

seen by Josh S. Rose

“Dance is very personal and needs to be captured with care, but also very technical. The light is always changing, the movement can go from fast to slow and a shape comes and goes very quickly.”

Josh S. Rose speaks with Jonathan Bergström

for LE MILE .Digital

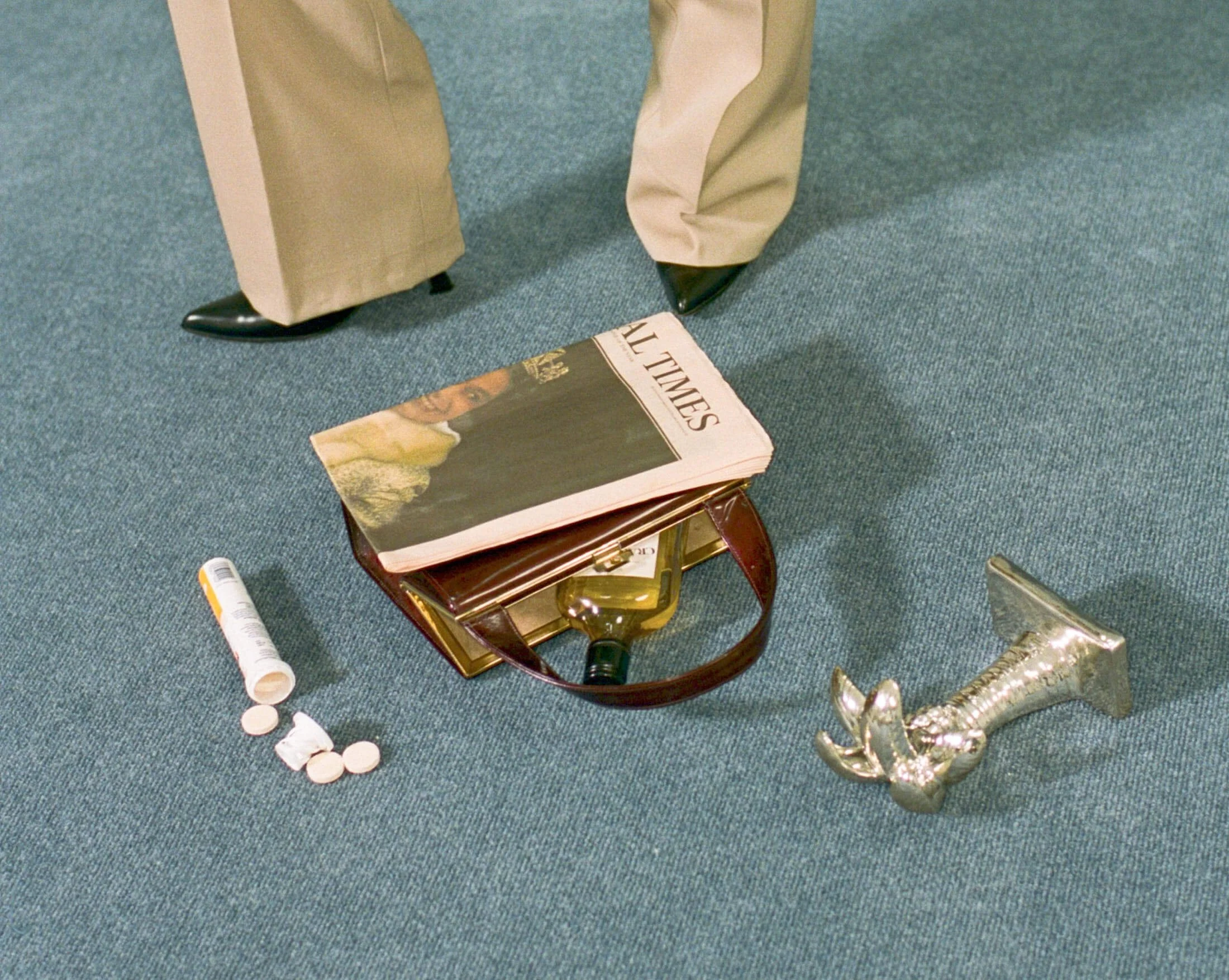

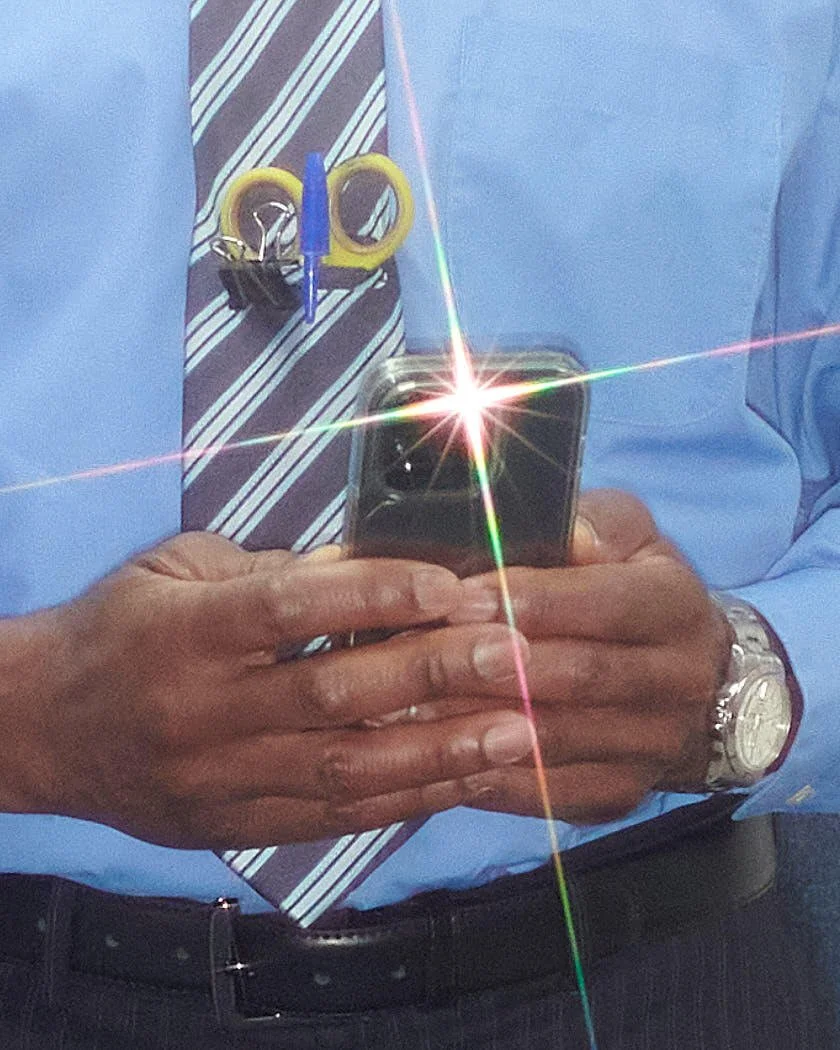

Compared to Tired, The Standouts feels more outward-facing. How did that change your role as an observer?

The Standouts is still me wondering out loud. In that work, I’m the outsider who quietly sits in the shadows and observes the louder, bolder, more assertive animals of the species. In all my photos, I feel like observation is key, but I think what might be felt in The Standouts is perhaps just a little bit more of an opinion. It’s not about all people, which a lot of art strives to be, it’s about a certain kind of person. But we all know this person, we even have a little of them in us, too. It’s not me, but it is something I recognize in me, in all of us. So, I’m observing others, but I’m questioning it inside myself, too.

In The Standouts, you describe behaviors such as running, shopping, and adding flair as efforts to “be more than who we are.” What made you want to examine these actions through this work?

I remember when I came of age and started finding myself at bars in my twenties, one of the things that stood out to me the most was the way people got louder as the night went on. To a point where, late into the night, a guy would just yell at the top of his lungs or a girl would take her top off, or cry performatively in public. It happened every time. And being, let’s just say less outgoing, it always seemed odd, behaviorally. I mean, I’ll be honest, I never liked it. But there’s a phrase, “We often dislike in others what we most dislike in ourselves.”

So, this is how I see people, or at least a subset of people, or subset of ourselves, as striving to be seen, heard and appreciated: look at me. But if I examine it, this is about me not really putting myself out there in that way and wondering about it, observing it, dealing with it.

I should talk about the stretching part. It’s purposefully rudimentary. It is supposed to feel almost clumsily done because it’s meant to show the thinking, the observation, and how when we do endeavor, it’s often less refined than we believe it to be, verging on rude, or abrasive. These are simplistic desires, being big. I’m just sort of anthropomorphizing it, having it over-manifest in them. There’s some Kafka in it.

When working on this series, did you find yourself observing people, culture, or behaviors, or all three at once?

All three are access points when I’m capturing for this series because some displays are more individualistic and others happen culturally. Going to the beach and being on display in a bathing suit is cultural, so is shopping or going to a museum. But running or standing on a wall with your arms outstretched is more of a personal choice that can be behavioral or even just one person’s colorful feather display.

The Standouts

seen by Josh S. Rose

The Standouts

seen by Josh S. Rose

Each of these projects presents endurance in different forms, physical, temporal, and social. Was that connection intentional?

Humans do have to contend with endurance. Doing things over and over again creates patterns and I put myself in positions to observe and shoot these patterns. I think what the question is keying in on is that there is also a human effect from this. I think that what I am often most intent on is how we respond to our need to endure in order to live. I imagine that is coming across in all of this.

Looking across these three bodies of work, what stands out to you now that may have been invisible at the start?

Movement has been a big part of my trajectory as a photographer. A lot of people know me through my dance work. I think what is coming out as my work evolves into series like this is that there is a deeper meaning to movement; there is more to it than the beauty of doing it gracefully. You can do that, but the full spectrum of how we move through life is on display through these works.

Are there any current works or cultural movements in music, film, literature, or art that feel especially inspiring to you at the moment?

I call my work “Technical Romanticism.” It’s an homage to the Romantic painters with whom I most identify as an artist. This was a time in art when artists were making works that captured the human response to the environment around them, with all the emotions and drama that that entailed. This reaction against order, reason and restraint is important in art. It empowers the emotional being and discusses the intersection of world events with its effect on us as human beings. People responding to their environments, it takes many different forms. But all of them feel inspiring to me. That is the direction my curiosity goes when I have a camera in my hands.

Tires

seen by Josh S. Rose

“What is coming out as my work evolves is that there is a deeper meaning to movement; there is more to it than the beauty of doing it gracefully.”

Josh S. Rose speaks with Jonathan Bergström

for LE MILE .Digital

all photography (c) Josh S. Rose

![Unknown [Gloria in Susanna and Marie’s New York City apartment] 1960s Chromogenic print 3 1/2 x 3 9/16 in. (8.9 x 9 cm) Art Gallery of Ontario, Purchase, with funds generously donated by Martha LA McCain, 2015 Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/c5552ea0-419f-42de-95d0-e72f76da9816/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Gloria+in+Susanna+and+Maries+New+York+City+apartment_AGO.121804-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment] 1960 – 1963 Color vintage print 9 1/16 x 7 1/5 in. (23 x 19 cm.) Collection of Cindy Sherman Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/158c7a10-a813-4aa0-a02b-d184a06c982b/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Susanna+standing+by+the+mirror+in+her+New+York+City+apartment_EXH.169577-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY] September 1966 Chromogenic print 5 1/16 x 3 9/16 in. (12.8 x 9 cm) Art Gallery of Ontario, Purchase, with funds generously donated by Martha LA McCain, 2015 Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/a1477c4a-2457-4789-a42c-d451bef2c0ee/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Lili+on+the+diving+board%2C+Casa+Susanna%2C+Hunter%2C+NY_AGO.121772-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Sheila and her GG Clarissa and friend, reading Transvestia] 1967 Gelatin silver print 3 5/16 x 4 5/16 in. (8.4 x 10.9 cm) Collection of Betsy Wollheim Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/7c014898-8ebf-49bc-8c17-92b403b88b9b/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Sheila+and+her+GG+Clarissa+and+friend%2C+reading+Transvestia_EXH.169756-Standard+Print.jpg)